Maíz Negro

“We grow this corn for the families who live and work here in Napa. It comes from Mexico and Peru. We call it ‘maíz negro’ and we grow it each year along with many other favorites.”

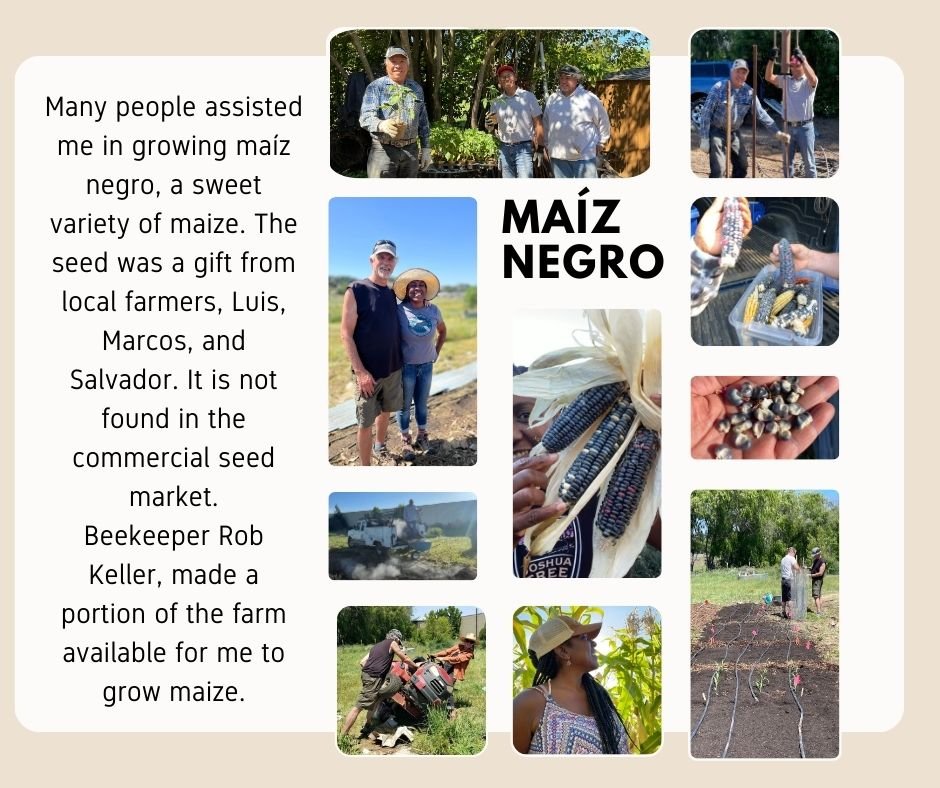

Luis Padilla, Marcos Garcia, and Salvador Gallegos grow diverse crops to feed food insecure families through a partnership with Presbytery of the Redwoods' Covenant Presbyterian Church in Napa County.If you’ve reached this part of the story, and happen to have received some maíz negro from the seed library, you should know where the seeds originate. Luis told me they come from Mexico, passed to them from friends and family that he, Marcos, and Salvador visit each year. They share culture, stories, and sometimes seeds. Luis describes this seed as a mix from Peru (the purple kernels) and Michoacán, Mexico (the black kernels). Each time they are in need of more seed to add to the stock they grow, they get some from friends back home. At their plot in Napa, they grow it organically and open-pollinated among other crops to strengthen and preserve the biodiversity in the genetics held inside. They’ve done this themselves for over 20 years. But in 2023, through our Partner Farmer Program, four participants grew out seed in Napa and in Oregon to help them to preserve this heritage seed that feeds food insecure families in our county.

Lauren Buffaloe-Muscatine holds three cobs of maíz negro in her hands, showing different colored kernels pointing to their genetic diversity, her smile is visible behind them.Background and Personal Connections

Napa County’s population of 136,000 is comprised of people of Hispanic, Latino, African American, Asian, Indigenous, and European ancestry. My own heritage descends from African American and Indigenous ancestry dating back to 1775. My intentions for the seed production course were to conduct a small-scale grow-out of a locally adapted seed as a pilot project of the Napa County Seed Library’s Partner Farmer Program.

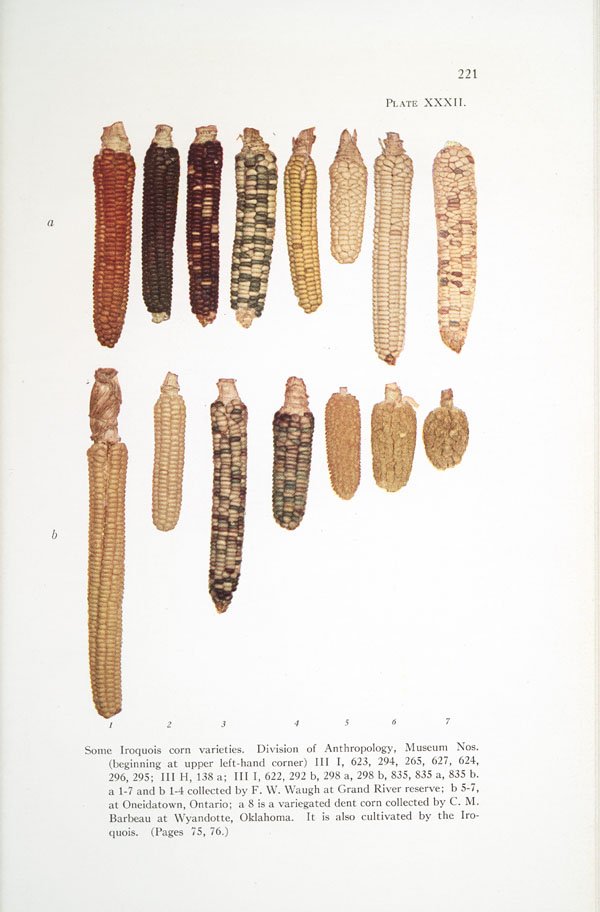

My goal was to produce enough organically grown seed from a developed landrace of maize with a connection to Napa County and to my own heritage as a descendant of the Mohawk, one of tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy, formally known as the Haudenosaunee.

My great-great grandmother Elizabeth Brown Johnson is the family matriarch on my mother’s side. She was born in 1845 and all of the women in my mother's line were born in Baltimore, Maryland, except my daughter, who was born in St. Helena, California. My great Uncle Tollie and great Aunt Joy, our family’s main historians, described her heritage as a descendant of the Mohawk (Haudenosaunee) tribe.I chose to grow a sweet variety of maize. (In this post I will alternately use the words maize, maíz negro, and corn to describe my chosen seed crop.) The seed I used is only sourced locally and not found in the commercial seed market. It is grown on a very small scale as a legacy crop locally adapted to our region. I selected maize to advance my farming skills and increase my knowledge of seed production. Maíz negro seed was given to me as a gift from veteran growers who are of Mexican and Latin American heritage: Luis Padilla, Marcos Garcia, and Salvado Gallegos. These growers, now retired from 60 collective years of city employment, grape farming, and other work, originally sourced this maize from friends living in Mexico as far back as the 1980s. They grow this maize organically at a small farm that they operate as volunteers and have saved and replenished their seed stock for over 30 years. On their small farm, they grow other types of crops as fresh produce. They donate some of the food they grow to the Napa Food Bank, and also deliver produce to underserved families directly to their homes. Their heritages originate from many Spanish speaking countries. Members of our community who experience food insecurity ironically often work in agriculture producing grapes and other crops for other people.

Cultural Origins and History

In this blog post, I’ll just give a sketch of the cultural origins and history of maize. For a full treatment on this topic, read the complete Seed Historian Report, that I wrote for the OSA’s Seed Production Course final project.

Mexican and Mayan Cultures

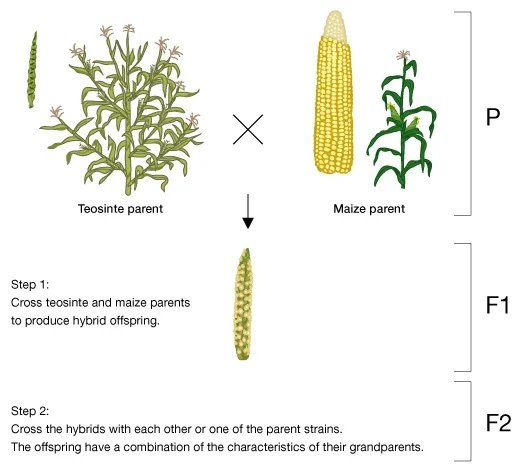

For thousands of years, indigenous communities have honored the sustenance that Earth has provided them throughout their history. Maize was first domesticated by native peoples in southern Mexico 5,000 to 10,000 years ago. Early civilizations created maize hybrids by cross pollinating plants from different varieties.

Maize is one of the purest inheritances of Mexican ancestry, and now represents an important part of the country’s gastronomy because of the great variety of species that exist. According to the National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity (CONABIO is its Spanish-language abbreviation), in Mexico, there are 64 types of maize, of which 59 are native, all with unique characteristics, with different flavors, colors, shapes and sizes. The taste, levels of starchiness and sweetness, and color varieties found among maize lends all kinds of creativity in its preparation. Maize is a key ingredient in the essential diets, beliefs, and traditions of many countries. Its uses range widely: as an offering; as a fresh food; as nixtamalized using limewater; as ground into flour; as boiled or fermented, or as distilled into drinks. Maize husks have a long history of use in the folk arts for objects such as woven amulets and dolls.

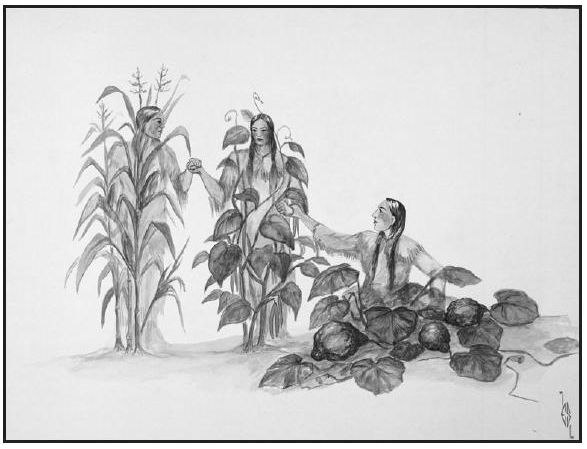

The Three Sisters by Ernest Smith. public domain.The Iroquois Confederacy (Haudanosaunee)

First Nations peoples in the northeast of North America (Turtle Island) have been growing maize for almost two thousand years. It seems certain that native farmers selectively planted types that grew in larger ears with more succulent kernels that could ripen in a shorter growing season. This allowed the maize culture to move northward into the Great Lakes region.

By the middle of the fourteenth century, corn served as the major crop for the Haudenosaunee who used it as the foundation of stable and productive agriculture across the region. Corn has been central to Iroquois culture, playing a pivotal role in the social, political, economic, and cultural arenas of indigenous life. It appears in key Iroquois oral texts including the Creation Story, the Great Law of Peace, and the Thanksgiving Address.

Throughout Iroquois history, women have been intimately linked to corn, beginning with its arrival on Earth. They were entrusted with its care and became thoroughly intertwined with corn as sustainers of life. In the Iroquois Creation Story, Sky Woman fell through a hole in the Sky World to the dark waters below, grabbing in her hands the seeds of several plants as she fell.

Corn appears again in the epic text of The Great Law, which describes the establishment of the Iroquois Confederacy. Iroquoia was in a state of almost constant warfare with communities taking up arms against each other in round after round of fighting and retaliation. The Peacemaker, a Huron from the north side of Lake Ontario, arrived in Iroquoia to propose a new governance system based on the ritual of condolence and community representation and participation in a central council.

Domestication of Corn and Wild Ancestors

The sweet type of modern maize (Zea mays ssp. rugosa) is different from the plant that scientists believe it originated from thousands of years ago. It is believed to have been derived from the Balsas teosinte (Zea mays ssp. parviglumis), a wild grass.

The Evolution of Corn. Source: University of Utah: https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/evolution/corn

Maize cobs uncovered by archaeologists show the evolution of modern maize over thousands of years of selective breeding. Even the oldest archaeological samples bear an unmistakable resemblance to modern maize.

Ancient farmers in what is now Mexico took the first steps in domesticating maize when they simply chose which kernels (seeds) to plant. These farmers noticed that not all plants were the same. Some plants may have grown larger than others, or maybe some kernels tasted better or were easier to grind. The farmers saved kernels from plants with desirable characteristics and planted them for the next season's harvest. This process is known as selective breeding or artificial selection. Maize cobs became larger over time, with more rows of kernels, eventually taking on the form of modern maize.

For a more complete discussion of this topic and more on maize’s Cultivation and Use, read the complete Seed Historian Report.

Growing Maize for Seed Production

Maize is a tall annual cereal grass that has a stout, erect, solid stem, large narrow leaves with wavy margins, and large elongated ears containing rows of starchy seeds. From mid-April through October 2022, I planted, weeded, watered, organically fertilized, and harvested a crop of viable, locally adapted maize seed. The maize I planted was a moderately sweet variety with predominantly blackish-blue kernels, occasionally dotted with speckled, deep red, and white kernels within its cob.

A local beekeeper, Rob Keller, made a portion of the farm in southern Napa where he keeps his hives available for me to grow maíz negro. The farm’s location was ideal because of existing inputs, isolation from other farms, and good weather conditions. The soil type is clay, like much of Napa County, with unknown fertility. Two years before, the field was planted, but untended. Prior crops volunteered as garlic, kale, radish, and fava bean. Calendula, bachelor’s buttons, and zinnias were planted as bee forage to supply the hives. Some California native plants grew at the edges of the planting area. Rainfall in the area the winter before planting seed was intermittent. From May through October, conditions were dry. Daytime temperature ranged from 75 to over 97 degrees F; evening temps were 40 to 55 degrees F.

Maize is monoecious and wind pollinated and needs proximity to neighboring plants of the same species to ensure ample pollen flow from tassels to fertilize silks and produce viable seeds. Nearly every day, light to strong winds blew in after the noon hour and remained steady until sunset. Corn is a highly outcrossing crop and requires an isolation distance of two or more miles to retain varietal characteristics. Farmers nearby my field grew produce 150 yards away, but they planted maize in June, more than 30 days later than my crop, so cross-pollination from their field was not a concern. Although the recommended population size to grow maize for seed production is a minimum of 200 plants, I had space enough to grow only half that amount. I planted a total of 110 seeds or seedlings into rows spaced 18 inches apart (with seeds spaced 6 inches apart) in an area of about 7 by 20 feet.

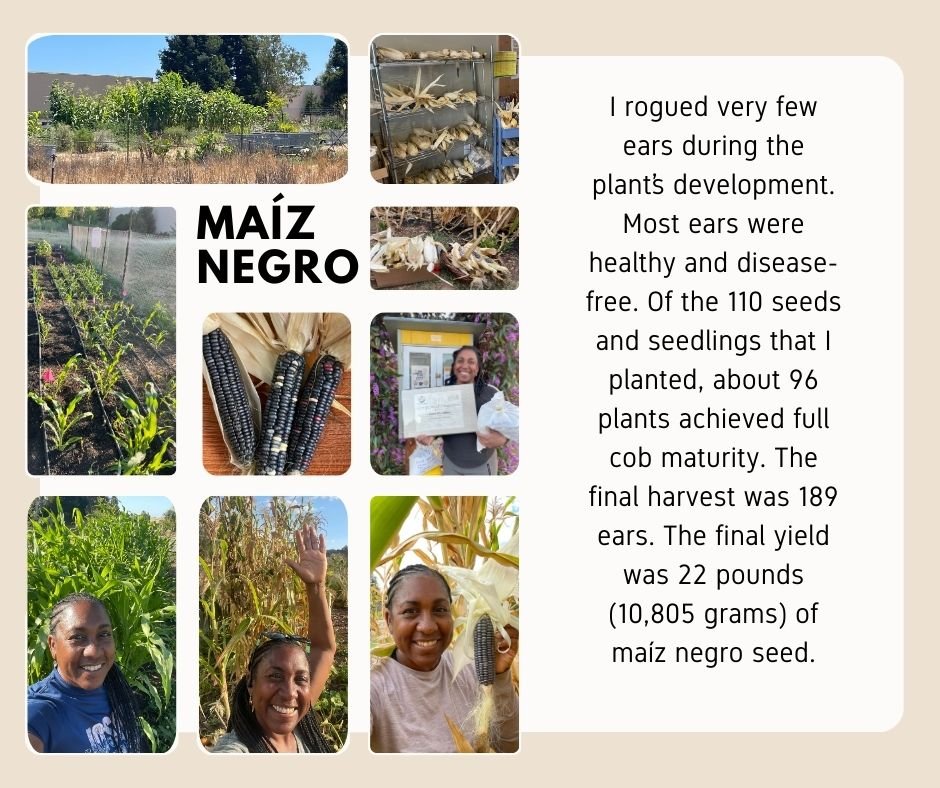

I rogued very few ears during the plant’s development. Most ears were healthy and disease-free. I did not select for any specific traits; I mostly grew for healthy plants and high yield. I removed about five ears that showed slight symptoms of pest damage or ear mold. We sampled only a few ears at the fresh, edible stage to evaluate its flavor, sweetness, and color. Notably, the kernels are white when young and fresh, but as they mature, they gradually turn blue and less often red or purple.

Of the 110 seeds and seedlings that I planted, about 96 plants achieved full cob maturity. Eight of these produced ears with only partially filled cobs. A few ears showed no pollination and did not set seeds. Two plants produced no ears. The ears ranged in size and quality. The ears with the best kernel development I grouped by length: 48 were small (up to 4 inches), 64 were medium (4 to 6 inches), and 40 were large (greater than 6 inches). Thirty-seven ears showed poor germination and kernel development. The final harvest was 189 ears. The final yield was 22 pounds (10,805 grams) of maize seed.

Final Reflections

Many people influenced and participated in my project, offering valuable information, advice, and labor in the field. My success was assured by these people: Eric McKee, Luis Padilla, Salvador Gallegos, Marcos Garcia, Rob Keller, Julie Kirkenslager, Jeff Hagar, Benito Garcia, Leonardo Ureña, Anayeli Cruz, Ana Galvis, Michael Lordon, Jared Zystro, and all the presenters and members of the OSA Seed Production Course.

The experience of growing seed with a large group of organic seed farmers and enthusiasts from six countries, learning and practicing together, was very special. The insight and resources I gained through peer-to-peer networking and individualized personal and professional mentorship was highly valuable.

At the project’s end, I felt joy and a deep sense of accomplishment and connection with the maize that I grew and with new knowledge that I discovered and practiced.

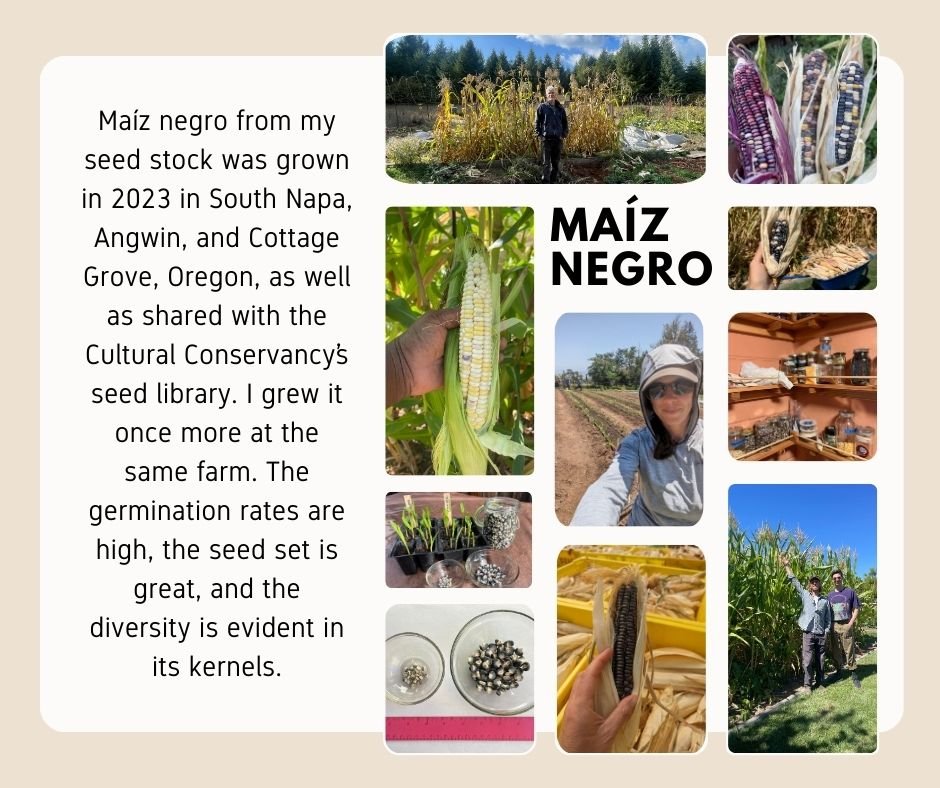

In the year that followed, the maíz negro from my seed stock was grown in 2023 in South Napa, Angwin, and Cottage Grove, Oregon, as well as shared with the Cultural Conservancy’s seed library. A few ears even made it to a group of farmers in Oaxaca, Mexico via a seed-saving friend. I grew the seed once more at Rob’s apiary and farm. The resultant germination rates were high, the seed set was great, and the diversity is evident in its kernels.

This intimate and deliberate task of growing maíz negro and saving its seed to share I hope will provide resiliency and renewal for others, and a continued feeling of peace for me.